Part of: Chernobyl accident , Nuclear Russia

MOSCOW/ SLAVUTCH, Ukraine – A “combination of negative factors” rather than excessive snowfall was the cause of the February 12 partial wall and roof collapse at Chernobyl’s infamous Reactor Unit 4, recent findings of two commissions that investigated the incident revealed. Notably, the risk of concrete slabs collapsing over the reactor halls of the defunct nuclear plant’s three other units had been discussed just one day earlier, on February 11, in Ukraine’s Slavutich. And Russia has three stations running Chernobyl-type reactors, RBMK-1000s – all three of similar or older ages and still in operation. How badly should Russia be concerned about its old stations’ safety?

Andrei Ozharovsky, Maria Kaminskaya, 03/03-2013

News that a portion of wall panels and roof collapsed at Unit 4 of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) came on February 12. Just one day before, the possible risk of some of the upper structures caving in on the reactor buildings housing the station’s Units 1, 2, and 3 – which were not themselves damaged during the catastrophic explosion of April 26, 1986, but were shut down in subsequent years – was discussed at a public hearing in the Ukrainian town of Slavutich, 50 kilometers from Chernobyl.

On February 26, a report stating the findings of two commissions convened to look into the causes of the February 12 incident was released on Chernobyl NPP’s website(in Russian), saying, in particular (quoted in Bellona’s translation):

“Snow load on the roof of the turbine hall at axes 50-68 from Range A to Range B did not at the moment of the collapse exceed the values established in the project and operating documentation of [Chernobyl] NPP.”

Instead, the report said, a truss failure – precipitated by a “combination of negative factors,” detailed in the findings – may have caused the collapse of a fragment of roof and walls at Unit 4.

The partial roof and wall collapse at Reactor Unit 4

On February 12, Chernobyl NPP’s press service reported an “abnormal situation” at the plant (quoted here verbatim):

“12.02.13. Partial failure of the wall slabs and light roof of the Unit 4 Turbine Hall occurred at 14.03 above non-maintained premises on the level 28.00 meters in the axes 50-52 from range A to range B. The area of damage is about 600m2. This construction is not critical structure of the ‘Shelter’ object.”

“There is no violation of limits and conditions of ‘Shelter’ object safe operation in accordance with the technological regulations,” the statement said. “There are no changes in radiation situation at [Chernobyl NPP] industrial site and in Exclusion zone. There were no injuries.”

Photographs released by Chernobyl NPP’s press service show that the incident occurred not far from Object Shelter – the concrete sarcophagus entombing the destroyed Reactor No. 4 – with the reactor’s vent stack, the all-too-familiar image from the site of the 1986 catastrophe, visible in some of the pictures.

A February 13 AP story cited a statement by Chernobyl’s spokeswoman Maya Rudenko that the affected area is about 50 meters from the sarcophagus.

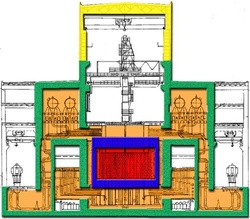

The four reactors at the station, each enclosed in a separate reactor building, are connected to one open turbine hall that served all four reactors.

A later statement (in Russian) from the station’s press service said work that was under progress at Object Shelter had been suspended and personnel removed from the site (quoted in Bellona’s translation):

“On February 12, following the abnormal event at the turbine hall of [Chernobyl] NPP, all works at Object Shelter, on the territory of its local zone, and at the assembly platform of the [New Safe Confinement], were ceased, and personnel removed from the site pending update on the radiation situation in the work zones. On February 13, [Chernobyl] NPP stated there were no changes in the radiation situation due to the incident that had taken place.”

The New Safe Confinement is an enormous arch-shaped structure being erected at the site, later to be moved over the existing sarcophagus, which was hurriedly built over the reactor to contain the 1986 catastrophe’s severe radiation hazard. Once in place, the confinement is hoped to serve as a more secure shield against the danger of radioactive substances leaking from the reactor remains and make it possible to dismantle the old shelter, which is deemed unstable and at risk of collapse.

A Bloomberg story of February 14 said Bouygues Construction – one of the two partners in the French consortium Novarka (Vinci Construction Grands Projets is the other half of the 50/50 consortium), which was awarded the New Safe Confinement project contract in September 2007 – removed its workers from the site as a precaution after part of the structure at Unit 4 collapsed. The story cited a company statement as saying that radiation levels at the site were within the normal range.

Work in the area where the New Safe Confinement is being assembled resumed on February 20, the plant’s press service said citing a written notice from Novarka management.

Two commissions’ report says a “combination of negative factors” precipitated collapse

Experts with two commissions that investigated the incident – one was convened on an order by the power plant’s director, Igor Gramotkin, and the other, as per a requirement of Ukraine’s State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate – concluded in their report that, based on the project documentation and operating documentation, as well as visual examination of the scene of the incident, a falling truss at Axis 50 from Range A to Range B may have caused the collapse of part of the roof over the turbine hall.

A number of negative factors likely led to the incident, the report said, including (in rough interpretation of the report’s specific findings): lack of reliable data on the actual damage sustained by the structural components of the roof during the 1986 disaster; possible failure in weld seams and excessive loads caused by partial displacement of some of the structural elements as a result of the 1986 accident; problems with some of the measures undertaken to ensure stability and rigidity of the truss; corrosion due to precipitation; displacement of a part of additional roofing and the resulting load redistribution, not provided for in the design; and other factors.

“The main reason that made it impossible to prevent the failure of the mentioned structures,” the report said, “was the lack of a possibility to carry out visual control of the technical condition of the structures due to the absence of safe access and the extremely hazardous radiation situation.”

The experts concluded, however, that the load-bearing elements adjacent to those that collapsed on February 12 were relatively stable, and that the incident did not affect the plant’s safety, did not endanger people’s lives and health or the environment, did not cause a stop to the operations, and is not considered an accident.

The commissions recommended further examination of the remaining supporting structures of the turbine hall to rule out any further failures, dismantling of the damaged side panels, and restoring the roof to prevent radioactive substances from spreading into the environment and to protect the building from atmospheric precipitation.

There were likely no significant radiological consequences from the incident, as official information confirmed. That the incident occurred in winter may likewise be considered a touch of luck; had it happened in the summer, it may have caused a new transfer of radioactive dust.

The Slavutich-based State Specialized Enterprise Chernobyl NPP is the entity responsible for the site, where some 2,600 personnel are currently employed. Work at the station did not stop after the temporary shield – Object Shelter – was built to isolate the exploded fourth reactor from the surrounding environment – nor after the remaining reactors were shut down. The station was not abandoned, left exposed to the elements to slowly erode and fall to pieces. But the buildings housing the shut down Reactors 1, 2, and 3 are old enough to start to crumble, too. This could well lead to a radiation accident at the site. The February 12 incident raised concerns over just how effective the mothballing measures have been.

Just how sound are other structures at the old plant?

In fact, the possibility of just such an event – a more serious accident, involving the collapse of upper structures of reactor buildings housing Units 1, 2, and 3 – was discussed in Slavutich just before the incident in the turbine hall of Unit 4.

The public hearing gathered on February 11 in Slavutich discussed one of the Chernobyl NPP decommissioning stages, a project referred to as “Final Shutdown and Preservation of Reactor Installations.” Reactors 1, 2,and 3 were shut down before their expected useful life terms had been exhausted, in 1996, 1991, and 2000, respectively. Stage 1, according to a description of the decommissioning program available on Chernobyl NPP’s website, involves the removal of spent fuel from the reactors and placing it into long-term storage – a step planned for completion no earlier than 2014. The spent fuel has now been unloaded from the reactors, and the issue of long-term storage is currently being worked out.

But even when spent nuclear fuel, the most dangerous type of nuclear waste, has been removed from a reactor, the reactor still remains a hazard. Mothballing the reactors and the most contaminated equipment constitutes Stage 2, until approximately 2028. The three undamaged reactors at Chernobyl will still require maintenance and regulatory control for the duration of the cooling period, or Stage 3 – until an estimated date of 2045, when radiation levels are expected to have naturally subsided to acceptable values. After that, dismantling and cleanup, Stage 4, will take until around 2065.

The plan, for Stage 2, is to dismantle the hoisting facilities and refueling machines, weighing hundreds of tons, remove the highly radioactive fuel channels from the reactors (450 tons per reactor), and dismantle the upper structures of the reactor buildings, which, project developers say, may deteriorate enough to cave in right on the reactors underneath, causing a serious radiation accident.

Speaking at the hearing, Chernobyl NPP’s First Deputy General Director Valery Seida said measures had to be taken to decrease the load on the structures of the reactor buildings.

“We need to dismantle the refueling machines, cranes, which present a hazard and may fall,” Seida said at the hearing.

In response to a question from Bellona, Seida said that after the March 2011 disaster at Japan’s Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant, Ukraine reviewed its NPP safety criteria, determining the need to take into account potential accident scenarios involving the less likely but more powerful earthquakes.

“A 6.0 magnitude earthquake can happen once in 10,000 years. This is a very unlikely event, but we have to be prepared for it. The NPP’s structures deteriorate with time and may not withstand such an impact. So we propose to dismantle them and lower the reactor buildings’ roofs to the level of the cast concrete,” Seida said.

“If we just leave everything as is, things will start crumbling down, just like the houses in the abandoned Pripyat,” Dmitry Bobro, first deputy director of the State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management, said, referring to Chernobyl NPP’s satellite ghost of a town that was entirely evacuated after the 1986 catastrophe. Slavutich was founded just a few months later to house Chernobyl employees and their families, displaced by the disaster.

Responding to a question from Bellona, Yury Malakhov, who heads the Kiev-based scientific research and design and engineering institute Energoproyekt and is one of the developers behind the Final Shutdown and Preservation project, said:

“The station was built quite long ago. The first unit has already run up, counting from the launch, 36 years. The engineered operating lifetime of the unit is 30 years. If nothing is done with it, building structures will continue to deteriorate.”

“Or we will have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that there will be collapses, and it will fall into the condition that the destroyed fourth unit is in,” Malakhov said.

It would have been quite unlikely for Bobro or Malakhov to expect their predictions to turn true less than 24 hours after that discussion. Yet, on the very next day, news came of the crumbled roof over the fourth reactor’s turbine hall.

Is there a lesson Russia should be learning?

Chernobyl’s Reactor Unit 4 was commissioned in December 1983. If not for the 1986 disaster, the reactor’s projected useful life term of 30 years would have just now been approaching expiration, ending in December 2013.

The 1986 disaster served as a tragic cautionary tale, a warning dreadful enough to eventually lead to the closure of those RBMK reactors that were built during Soviet time outside Russia – at Chernobyl and Lithuania’s Ignalina NPP, where two reactors of the RBMK-1500 series were shut down in 2004 and 2009 to comply with the European Union’s requirements for Lithuania’s accession to the union.

But Russia continues to operate altogether 11 reactors of the Chernobyl type, RBMK-1000, with seven of these running on licensing extensions issued after the expiration of their 30-year life spans.

These units operate at Leningrad NPP, near St. Petersburg, in Russia’s Northwest, and Kursk and Smolensk NPPs, in Western Russia. Most of them are older than Chernobyl’s exploded fourth reactor. Only Unit 3 at Smolensk NPP and Kursk’s Unit 4 are about two years younger than their ill-fated Chernobyl counterpart. The rest have more years behind them.

The latest developments at Chernobyl NPP show that a nuclear power plant’s building structures can fall into decay and collapse. It is a grim reminder that continuing to operate RBMK reactors is dangerous and threatens the risk of new radiation catastrophes. The sheer age of Russia’s RBMK reactors would suggest that the reactor buildings, the turbine halls, and the reactors themselves may be just as vulnerable to deterioration and failure, and in just as bad a need of close attention.

Experts and environmental organizations alike have repeatedly demanded a stop to the dangerous experiment that the continued operation of RBMKs is. These demands are ignored by the Russian nuclear industry – just as Chernobyl’s 1986 wake-up call was ignored then. Surely, the latest incident at Chernobyl would serve as a lesson Russia will not choose to ignore?

http://www.bellona.org/articles/articles_2013/chernobyl_roof_collapse_report

Залишити відповідь